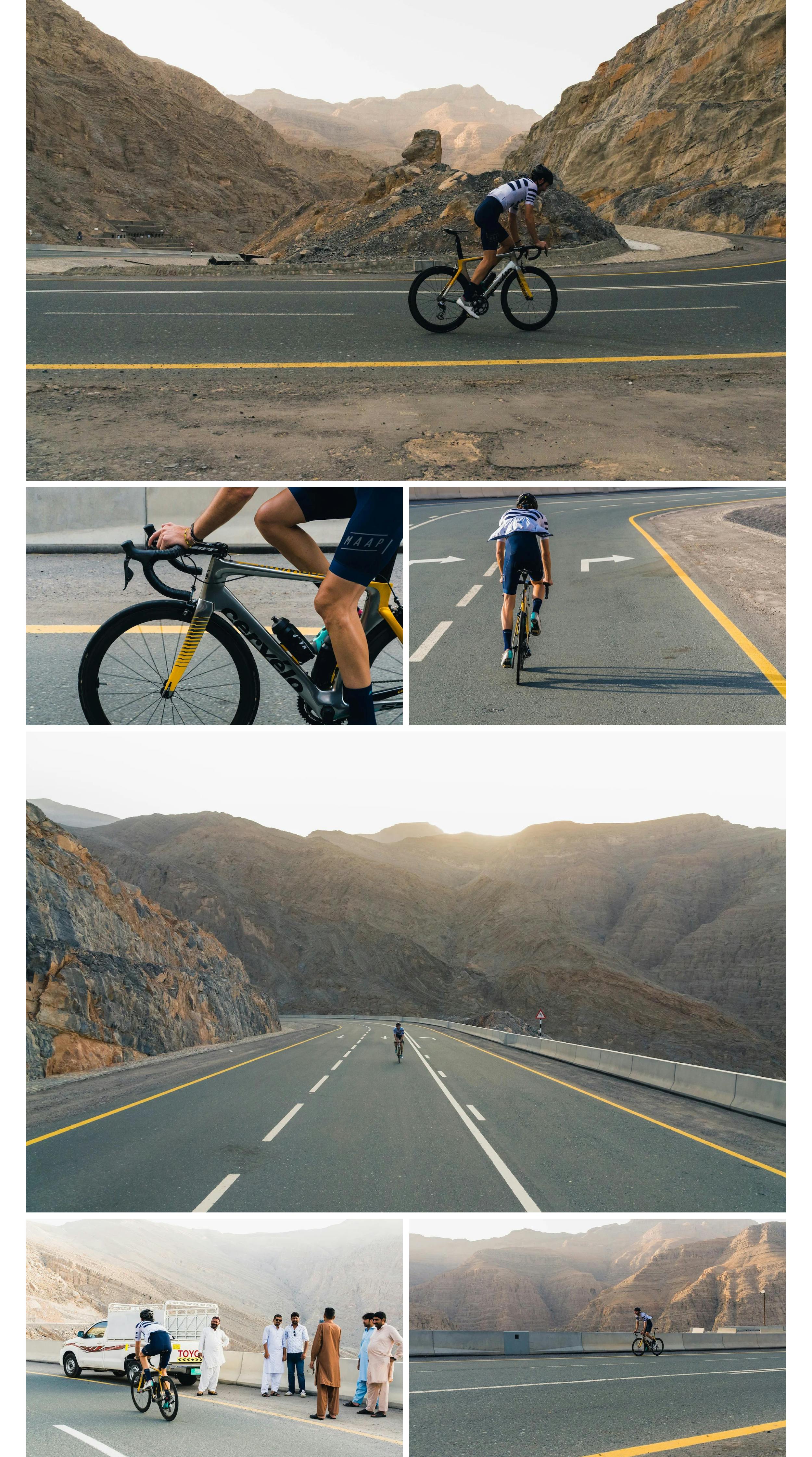

CLIMBING IN

THE FURNACE

August 10th, 2017

Photography by Andrew Laity

It’s perceived to be completely flat, which is mostly true. But just like in the Netherlands, the Dutch will always point to Amstel Gold Race as proof there is in fact elevation gains to be made while riding on their roads. Not many people are aware that in the UAE we have a HC Category Mountain located in Ras Al Khaimah which is similar in length and gradient to Col du Tourmalet or the Col du Galibier.

Here are the details:

Name: Jebel Jais

Distance: 19km

Average gradient: 5%

Elevation Gain: 997m

The Jebel Jais is on Strava. The KOM is currently held by Roman Van Uden with a time of 46 minutes 19 seconds which is totally mental.

To ride the mountains here in Dubai you need to want it. For starters, you have to wake up early when most are coming back from the dance floor and to then drive an hour and a half by car has always put me off. Personally, I would much prefer to be on the dance floor. And secondly, I don’t have a car. For 2 years I put off riding up the tallest mountain in the UAE because I could not get my head around the idea of needing to drive that far to suffer on a mountain. Previously, when I lived in London, a 90 minute flight from one of the airports would either have me in the Dolomites, Alps or Pyrenees.

For me, the snooze button is not an option. It stopped becoming one when I started riding with Marcus Smith of Innerfight Gym. There was once an occasion when I missed a ride because I opted to snooze the alarm instead of getting out and enjoying the bike. Unimpressed, he sent me a link to one of his podcasts where it was made clear that, “when you go to bed at night you set an alarm for the following morning, and that is your first goal of the day. If you hit snooze you have failed at the day's first task and you set yourself up for further failures!”

With this mindset now firmly installed, I was stumbling about my apartment at 2.30am in the dark having managed a pitiful 4hrs sleep. Light from the Burj Khalifa, one of the world’s tallest buildings, poured into my apartment from the balcony window. It’s not the classic desert sunrise I’d like to be describing to you right now but it did the trick. I’d been meticulous in my preparation the night before, laying out all my kit in perfect order. The obvious choice of kit for a day riding in the furnace was the M-Flag Pro Light Jersey. I like to tell myself that the team designed this jersey for me as a consideration for the weather I ride in for large chunk of the year. Sadly, this is not the truth. It sounds good, though, doesn't it?

Upon arriving at Jebel Jais, I decided to start 10km from the base of the climb. This would allow me to actually wake up and also start turning the legs a bit before the climb started. There was a small changing facility where I was able to apply some sunscreen and change into my kit. The temperature was already 34 degrees, and it was only 4:45am. I knew I was going to be in for a long ride.

I rolled out from the car park with good legs. I can always tell within the first 15-20 pedal strokes if I am going to enjoy my bike ride or not; and, thankfully, the first few rotations of the day were strong. I was feeling good. The day was going to be brutal, no question. But my legs, lungs, head, and heart we’re all ready to ride.

A few kms into the climb, the simple joy of riding solo really set in. Taking on the climb by myself was a welcomed experience. To look around and take in some rare scenery where only Earth’s toughest survivors have found ways to thrive was deeply inspiring. It’s what had been missing from my riding here in Dubai.

With just my thoughts for company and my breathing for entertainment, I needed this ride. Since moving to Dubai two years ago, I had to adapt to a pace of life which was more accustomed to the Formula 1 Circuit in Abu Dhabi. It’s hard to know what you need if you’re unable to pause and create space for reflection. Riding my bike on this barren landscape felt like slow motion, like I’d finally found time to pause and enjoy the sort of pace where thoughts could be processed and feelings felt at a more meaningful level. It gave my body the calibration that it had been desperately asking for.

The gradient kicked in and my legs started to feel like they were going to bail out on me. I knew that I now had 19km to the top and so I started to relax and remember to keep myself hydrated. At this point, the faucet was open. I was losing more water to the extreme heat than I could take in. With the temperature continuing to climb, hypnotic waves of vapor were beginning to rise off of the tarmac in the distance. Though I’ve only been on the bike for a little over 10km at this point, it was time to open up the jersey zip and let it flap in the warm air.

I run a 56/42 chainring as standard, such is the nature of the riding that I do here. Training on an 8km cycling track in Nad Al Sheba and going round and round and round it for hours on end means a strong, grinding style of riding.

The first thing I needed to do when I decided to tackle this mountain was change the setup, so I dropped the bike in at the workshop and had them install a 52/36. This way I could spin up the mountain without any issues – at least in theory. I was fortunate enough to see that a good friend of mine from CeramicSpeed, Rasmus Bækvad Gjærløv, who was in the store at the time and who helped me to make my bike even more efficient. He said, “you’ll appreciate this tomorrow!” and as I hit the first switchback of the afternoon I definitely did.

I don’t look at numbers on my computer. I like to check them occasionally but I don’t let them control me. Watts is the language of cyclists here in Dubai. Everybody talks about numbers. It’s obsessive. But for me, it’s a lot of nonsense.

I ride my bike because I like to disengage from stats and noise and ride my ride. I don’t feel comfortable with measuring the time I spend on my bike through the power that I produce.

And so, with that in mind, I turned the page on my GPS unit so that it showed only the time of day and the most important figure I needed to monitor – temperature!

While taking in the landscape around me, I noticed nothing but bone dry rocks and stones. The environment was completely alien. How does life exist here? Does life exist here? A friend of mine, Paul Gamble, said via text the day before, “You are going to climb Jebel Jais in July? Are you crazy?!” I was starting to realise why he was concerned.

The Jebel Jais is normally only frequented by cyclists between September and March when temperatures are low enough for you to get up it in time to descend back down before it gets too hot. Yet, here I was, in the peak of summer, looking at the temperature now screaming past 40º celsius with still another 10 km to go until the top. I decided to get a move on and turned the pedals a little harder. The views can wait until winter.

As I hit another switchback, I could see I was getting closer to the summit. With close to 5 switchbacks remaining, there’s a tower on the summit similar to the one found on Mont Ventoux which gave me something to focus on. Unexpectedly, 3 cyclists flashed by descending down the mountain. Was I hallucinating? Surely not? I looked down below me to watch how hard they attacked the hairpins. BOOM! Suddenly, one of the guys had a blowout and crashed at high speed as the temperature in his rims got too much. This was a clear reminder: we’re riding in an oven.

Despite feeling good I still needed to get to the top before attempting a 19 km descent in 44º degrees so I pressed on with around 3 km to the top.

I reached the summit with mixed emotions. Mentally and physically, I was cooked yet deeply satisfied. For 2 years, this climb has been a distant possibility. Now, I’m here, sitting on top of the UAE looking across the barren land as the tarmac radiated the immense heat. With my skin beginning to bake, I had time for a quick can of Irn Bru, now customary when riding mountains for MAAP, before starting my descent back to the foot of the mountain.

Having had to endure these intense desert temperatures for a couple of years now, I’ve picked up a few key tips for surviving the furnace:

When tackling a fast downhill, I’ll always remember those words of Brian Holm. I kept reminding myself of staying glued to the road while I thought about my rims overheating like the poor guy who attempted to descend before me. The jet black road had now reached lava like conditions as my tyres were genuinely starting to stick to the road.

Just as I approached the final part of the descent and started to relax, I swerved dramatically at 70km/h to avoid a mountain goat that had strayed across the road. The Arabian tahr lives on steep rocky slopes of the mountains across the UAE and Sultanate of Oman at altitudes of up to 1,800 meters above sea level. As if I was not already warm enough, my heart rate was given one last burst of anxiety to deal with before closing out the descent.

If you can endure the early rise and journey, the Jebel Jais is well worth skipping the night clubs in order to dance on the pedals at the top of the desert looking down upon the rolling dunes and arid desert landscape.

Riding in these extreme conditions was nothing but a lesson in how to ride well, taking me to the depths of what my body could physically produce in temperatures which demanded the most of me.

In hindsight, this was the therapy that I needed. Dubai’s a lovely but demanding place to live and this change of pace allowed me to focus my attention on moving forward – while processing a draining but truly developmental couple of years in the Middle East. With your bike and a good climb, I believe solitude can be an amazing thing.

When I got back to the car with nothing left to give I knew I was ready to return to the pace of Dubai with a new focus.